By Carrie Smith and Lisa Stead

We appreciate that we are a little late coming to the party on this one, but we have just come across this article in the Guardian - Online is fine, but history is best hands on (via the excellent http://archivesinfo.blogspot.com/). The article discusses the importance of seeing the original document over an online version. Although it makes some sensible points, points which have been made frequently on this blog, for example that during research in an archive:

“Perhaps another document will come up in the same batch, perhaps some marginalia or even the leaf of another text inserted as a bookmark”.

The author calls this the “serendipity” of research and certainly there is an element of unexpected discovery when undertaking archive work, however, the argument for seeing the original can be put in more concrete terms than the “mystery” being lost in online versions. What can be lost are slight differences in shades of ink colour, watermarks, water stains even etc – the genetic makeup of the document can be lessened. That said, the problem with Hunts argument, aside from its slightly melodramatic reverence of the ‘original’, is its unpleasant derision of the non-scholar, he writes:

“Why sit in an archive leafing through impenetrable prose when you can slurp frappucino while scrolling down Edmund Burke documents?”

The unpleasantness of this statement, even on the level of a physical shudder at the noisy, uncouth “slurp” of the person on the street, is offensive. It is the underlying message about access, however, that is worse. Although Hunt refers to the British Library, which is a public library, Hunt is unhappy with the public access search engines provide, he writes:

“the arrival of search engines has transformed our ability to sift and surf the past. What once would have required days trawling through an index, hunting down a footnote or finding a misfiled library book can now be done in an instant”

One commentator picks up on this and responds:

“Thus making this information accessible to people who aren't full-time academics and/or living in London. God forbid, eh?”

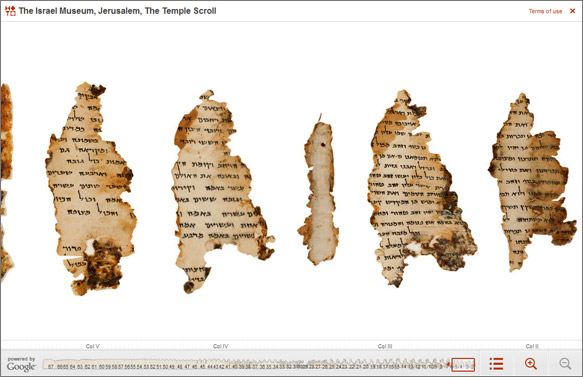

There also seems to be an element in the Hunt-esque argument of a sense of unfairness in the ease of access for the new generation of scholars, researchers and (again, god forbid) non-affiliated ‘ordinary’ interested people. As if, because the archive was formerly often something difficult to access, something that required travel grants, networking, extensive planning and a big investment of valuable time for the individual, it should equally represent a right of passage for the next generation. With this element of difficulty removed, the argument seems to suggest that ease of access somehow automatically will equate to lazy scholarship, idly flicking through sacred manuscripts on Iphone apps. The view that location and context for access fundamentally impacts upon ‘proper’ academic contemplation seems a difficult one to support, however, especially since there seems to be no consideration of any negative consequences that the hushed environment of the archive in which the academic seemingly sits in reverence, ‘leafing through impenetrable prose’ (all worthy scholarship should deal with this sort of prose, obviously) might have upon interpretation. Is it not possible that aura inspires a reverence that’s perhaps not always deserved, or that the sheer difficulty of access and the time/money/effort that goes into many archive research trips encourages the researcher to make links, connections and observations that aren’t always justified by the material, simply to make the effort worthwhile?

Although some of the reactions to this article were political, regarding Tristram Hunt’s position in the labour party, many were simply unsettled by Hunts preference to limit access to important documents to those who have the travel grants/geographical or scholarly access. Although seeing the original document is an important enterprise, the widening access new technologies allow and also the protection for fragile documents is of equal importance.

From a garden shed ‘archive’ to preservation for future generation of film historians and eager audiences… Non literary, but interesting archive related news nonetheless: a lost early Hitchcock film has been discovered in New Zealand and screened for the first time in Hollywood.

From a garden shed ‘archive’ to preservation for future generation of film historians and eager audiences… Non literary, but interesting archive related news nonetheless: a lost early Hitchcock film has been discovered in New Zealand and screened for the first time in Hollywood.